The story of the past is inevitably selective and this often results in some individuals being given, perhaps, undue prominence whilst other very significant figures end up being marginalised. Accounts of later English Puritanism have often ended up focusing on the likes of Richard Baxter (1615–1691), John Bunyan (bap. 1628, d. 1688), and John Owen (1616–1683), leaving others, who in their day were highly significant, to almost disappear from the historian’s view. One of the positive trends in more recent accounts of the Reformation and post-Reformation periods is to bring centre stage some of those who previously had been left waiting in the wings. The result is a new appreciation of the rich legacy that has come down to us and, in the case before us, a glimpse into how the Restoration church settlement might, so very easily, have been much more Presbyterian in nature.

November 2025 marks the four-hundredth anniversary of the birth of one of England’s most important Presbyterian ministers: Dr William Bates (1625–1699). He was born in Bermondsey, London, in the year that Charles I came to the throne. England was about to enter a period when a number of unresolved issues in the Elizabethan settlement would give rise to competing visions of what further church reform should look like. During his childhood, these fault lines were beginning to open with enormous consequence.

Not yet eighteen, in 1643 Bates matriculated at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, just as the first English Civil War was getting under way. This institution had been founded in the late sixteenth century and had grown to be one of the largest Cambridge colleges, famed as a nursery of Puritanism. As the nation polarised, its Master, Westminster Assembly member Richard Holdsworth (1590–1649), was forced out because of his royalist sympathies. Laudian policies had left their mark on Cambridge in a variety of ways but now the balance of power had shifted. By the end of the year, William Dowsing (bap. 1596, d. 1668) embarked on his iconoclastic work of purging the Cambridge churches and college chapels of images and carvings which were regarded as idolatrous and superstitious. Dowsing’s journal records that there was nothing to be done in Emmanuel, something unsurprising for a college favoured by the godly. For unknown reasons, Bates would move to the smaller Queens’ College, receiving his BA in 1645 and his MA in 1648. There he could benefit from the significant investment in the library and the presence of students who were Protestant refugees fleeing Germany and Hungary. (The often-absent continental context of the history of this period can add so much to our appreciation of it.)

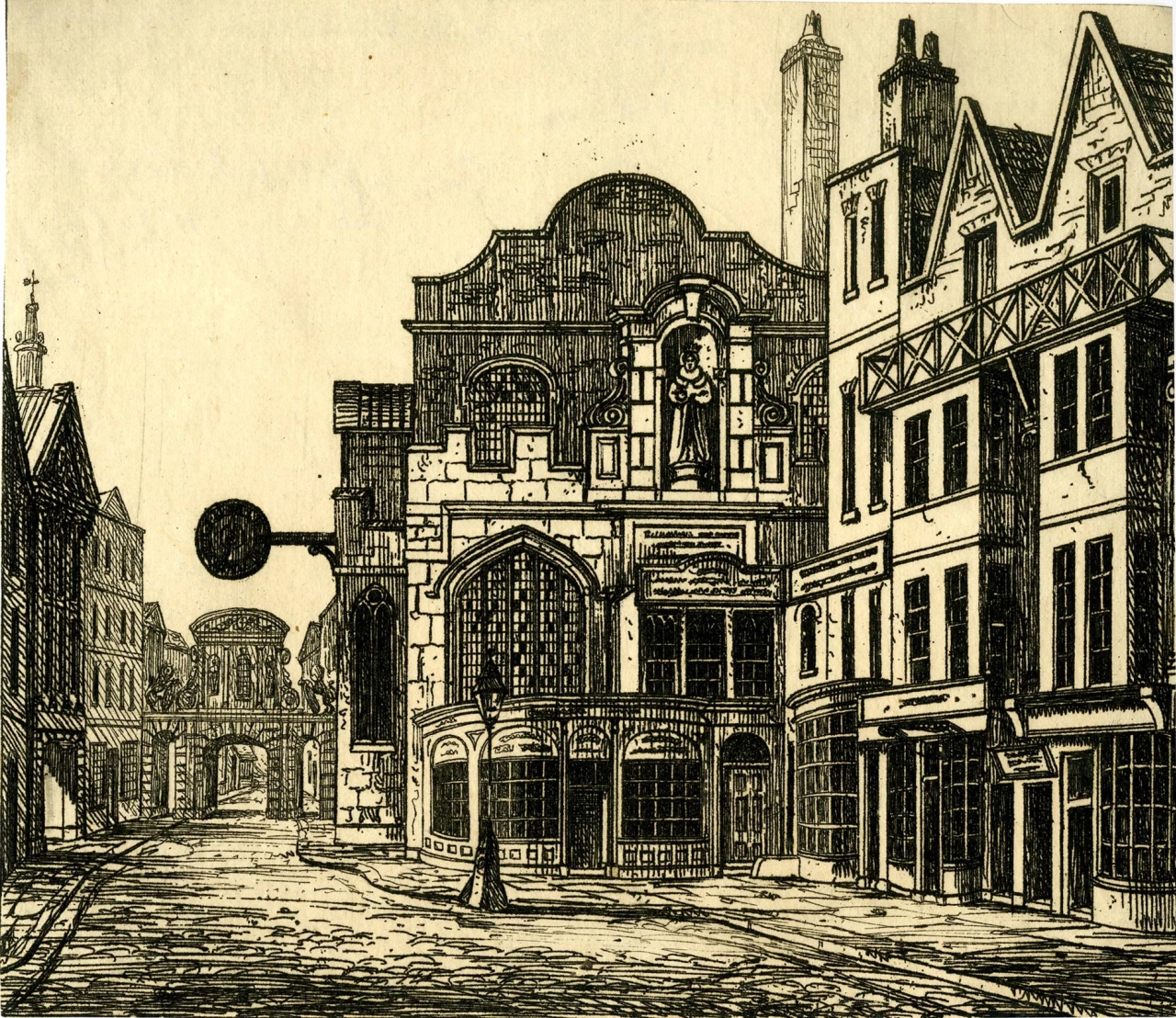

In 1649, at the beginning of the English Republic, Bates returned to London serving as a minister in Tottenham before being appointed minister of St Dunstan-in-the-West, sometime in the early 1650s. St Dunstan’s was a large medieval building on Fleet Street in what was a comparatively wealthy parish. Some very significant ministers had occupied its pulpit before him. William Tyndale (c. 1494–1536) had preached there on a regular basis when he spent some months in London engaged in his early translation work on the New Testament. In more recent decades, when Bates was a young boy in the city, the poet John Donne (1572–1631) had been its vicar, and in the late 1640s the prominent Independent divine William Strong (d. 1654) had ministered there. The parish churchyard was a significant centre of bookshops, particularly associated with legal texts due to the nearby inns of court. His ministerial friend John Howe (1630–1705) described Bates as a ‘devourer of books’ and it is easy to imagine him acquiring some of his very significant library at this time. Despite the loss of books valued at £200 to the Great Fire of London in 1666, after his death his substantial library became the centre of the collection of what is now Dr Williams’ Library (previously based in London but now relocating to the John Rylands Library at the University of Manchester). Amongst Bates’ books was what is now an incredibly valuable first folio of Shakespeare’s plays from 1623 and there is every indication that Bates enjoyed reading and annotating this volume with its historical plays, tragedies, and comedies. This is yet further evidence to debunk some of the general stereotypes of rather dull and humourless Puritans.

Old St Dunstan-in-the-West © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Bates lost a daughter in early 1658 and, in the months that followed, the nation entered a period of unrivalled political turmoil and confusion. In the late 1650s, London Presbyterians slowly regained a position of influence just as the experiment with republican government was coming to an end. According to Richard Baxter, Bates was one of the ministers in London who was instrumental in building support for a restoration of the monarchy. For his role in this, Bates was rewarded by being appointed as a royal chaplain and was recommended for the award of Doctor of Divinity from the University of Cambridge. In Charles II’s initial Declaration of Breda there had been promises of concessions to tender consciences and it seemed as if compromise might see Presbyterians ‘comprehended’ within the national church by granting enough flexibility to allow them to worship and minister within it. However, the Presbyterian position was far less secure than many thought and the London ministers repeatedly found themselves trying to negotiate on an agenda set by the bishops and the court. Despite this, Presbyterian hopes remained high when the King’s Worcester House Declaration of 1660 proposed flexibility on the liturgy and clear limits on episcopal power. Bates was one of London ministers to sign a declaration of thanks to the king for these indications of an inclusive settlement. Offers of preferment were made to a number of key Presbyterian leaders, with Bates promised the deanery of Lichfield. However, attempts in November to put the Worcester House Declaration into law failed and this marked a significant turning point in the fortunes of Presbyterians.

In the new year, Gilbert Sheldon, the new bishop of London, moved to enforce the supervision of his clergy, especially those with Presbyterian sympathies that led them to reject episcopal reordination or to raise scruples over the prayer book. Bates attempted to show a measure of compliance by insisting that in his services there were three scripture readings as well as the reading of the Ten Commandments and the Creed. In April 1661, King Charles convened a conference on the liturgy between Episcopal and Presbyterian divines at the Savoy on the Strand at which Bates was an important participant. Despite three months of lengthy debate, no agreement was reached and nothing substantial was conceded to the Presbyterians. Instead, there was a dramatic move towards a more restrictive church settlement.

Elections in the spring had returned a new Parliament that would become known as the ‘Cavalier’ Parliament. When it gathered in May it launched a parallel assault on Presbyterians and Congregationalists, one designed to crush any remaining hopes for a more moderate church settlement. For example, the Act of Uniformity required the following of all clergy: rejection of the Civil-War era Solemn League and Covenant; acceptance of only Episcopal ordination as valid; and unqualified assent to the exclusive use of the Prayer Book in all places of worship. If this had not been done by St Bartholomew’s Day (24 August) they would automatically be removed from their positions. Consequently, Bates was among the 1,000 or so clergy, schoolmasters, and college fellows who chose to give up their positions rather than conform to these stringent requirements. They joined around 1,000 others who had been ejected for various reasons since the Restoration.

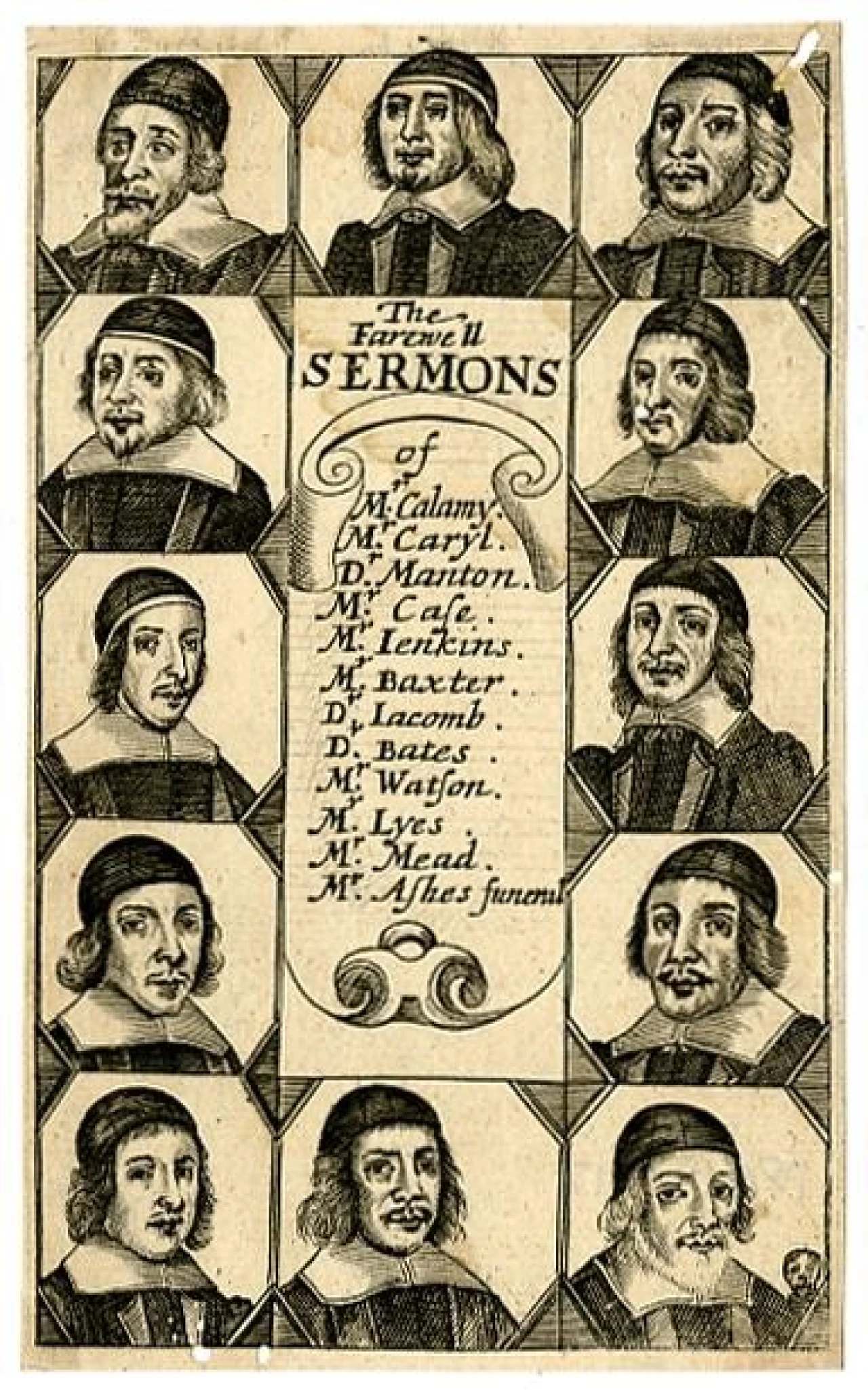

Samuel Pepys recorded hearing Bates preach in London © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

The famed London diarist Samuel Pepys (1633–1703) was among those who went to hear Bates preach his final Sunday sermons at St Dunstan’s. On 10 August 1662 he heard him deliver ‘a most eloquent sermon’ and the following week, on a wet summer’s day, he returned to hear him preach morning and evening to a packed congregation. Pepys was surprised that Bates said so little about the political circumstances that was about to result in the ejection of so many clergy. Perhaps Bates’ veiled speech went unnoticed as he concluded the sermon with a reference to the ‘League’ between God and his people and the ‘Covenant’ which opened the way to heaven. (The Act of Uniformity required ministers to renounce the Solemn League and Covenant.) However, what was unmistakeably clear was his statement that the source of his non-conformity lay in a ‘fear of offending God’. Presumably this was because conformity would require him to renounce his presbyterial ordination, accept a particular form of episcopacy, and to make exclusive use of the Book of Common Prayer. By the end of the year Bates’ farewell sermon was in print along with the sermons delivered by other ejected ministers who were known as Bartholomeans.

Title-page to an edition of 'The Farewell Sermons of the Late London Ministers' (c. 1662-3); Bates is included among the portraits of twelve dissenting ministers. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

After this ‘Great Ejection’, Bates, like many other ministers with Presbyterian convictions, took the path of dissent, continuing to minister in private conventicles. According to official government reports, Bates participated in a number of conventicles in London, some of which were near to his former incumbency of St Dunstan-in-the-West. For example, in February 1664 he participated at a fast held in a house in Whitefriars alongside Thomas Manton (bap. 1620, d. 1677) and Matthew Poole (d. 1679). Those in attendance included the Countess of Exeter, Lord Wharton, Sir William Waller and Richard Hampden. In response to activity like this, new legislation passed through Parliament. The Conventicle Act of 1664 fined those who participated in gatherings for worship outside the established church. The Five Mile Acts of 1665 barred nonconformist clergy from coming within five miles of their formal pastoral churches.

Having now also lost his wife, in the summer of 1664 Bates married Margaret Gravenor from the nearby parish of St Giles Cripplegate. He remained one of the principal figures involved in negotiations for various schemes for comprehension and toleration. In the late 1660s, with the likes of Baxter and Manton, Bates held out hopes of a more inclusive national church. Others, often Congregationalists and younger Presbyterians, thought such a resolution unlikely and instead sought toleration outside the national church.

In early 1669 there had been something of a lull for Dissenters in the wake of Parliament’s failure to renew the Conventicle Act. With this, the number of illegal gatherings for worship in London increased. Bates participated in a preaching lecture in Hackney with other well-known nonconformists like John Owen and Thomas Watson (d. 1688). With the established church pressing for religious uniformity, in 1670 the Cavalier Parliament passed a more stringent second Conventicle Act which came into effect in May. This Act significantly increased fines for dissenting ministers and those who allowed their homes to be used for unauthorised religious meetings. Magistrates were empowered to use force to enter any buildings where a conventicle was suspected. Furthermore, it imposed fines on magistrates who neglected to enforce the Act. Most controversially, it provided financial incentives to those who provided information that led to a successful conviction: informers were rewarded with a third of the fine that was levied. Up until this point, relatively few Presbyterians or Congregationalists found themselves in court because attention was focused on suppressing Quakers and Baptists. This was changing but, at least in London, the authorities initially struggled to enforce the new statute.

There was some hope that the king might be persuaded to abandon the Conventicle Act in response to a massive loan made by Dissenters to a financially strapped monarch. Bates contributed some £500 to what became known as the Dissenting Subscription of 1670. In total £40,000 was loaned to the king with the hope that this gesture might dispose him towards more favourable religious policies. In response, Charles promised to try to alleviate their plight and, in March 1672, a brief period of royal ‘Indulgence’ was proclaimed. Going against the wishes of Parliament, Charles II used his royal prerogative to suspend the penal laws against Dissent and allowed for licenses to be granted to Nonconformist ministers to enable them to meet in stated venues. The loan seemed, at least in some measure, to pay off. Bates was one of four Presbyterians that met with the king on the afternoon of 28 March in order to express thanks. In May, Bates received his licence as a Presbyterian teacher for a meeting in Hackney. These new freedoms gave Dissenters a new lease of life. Bates was appointed to participate in the famous weekly Merchants’ Lectures at Pinners’ Hall in Broad Street. These weekly lecturers on Tuesday mornings saw Bates and other Presbyterians like Baxter and Howe cooperating with Congregationalists like Owen.

In the early summer of 1673, the Cavalier Parliament voted down the king’s Indulgence. However, the respite of the previous year had allowed Protestant Dissent much needed breathing space to strengthen and establish itself. Furthermore, the conversion of the heir of the throne, James, Duke of York, to Roman Catholicism and the rise of French Absolutism resulted in less direct hostility to Protestant Dissenters. However, fresh efforts alongside Baxter, Manton, and Poole to find an accommodation with some of the conformist clergy in April 1675 came to nothing. Some of Bates’ most important works date from this time. From these, it is clear that the lack of contemporary awareness of Bates as a theologian cannot arise from an absence of a significant corpus of published writings. His works from this period include: The Harmony of the Divine Attributes (1674); Considerations on the Existence of God and the Immortality of the Soul (1676); and The Divinity of the Christian Religion (1677). An examination of these treatises challenges another stubbornly persistent myth about seventeenth-century Reformed orthodoxy. In the old Calvin versus the Calvinists paradigm latter seventeenth-century theological writing was often dismissed as rather cold, rigid, and speculative scholasticism. However, these works actually show Bates employing the scholastic method in order to encourage and edify. As he put it in the preface to the first of those works, his aims were ‘to inflame us with the most ardent Love to our Saviour’ and ‘to persuade us to live for Heaven’. Alongside his writing, Bates remained a celebrated preacher, delivering, for example, the sermon at the funeral of Manton in October 1677.

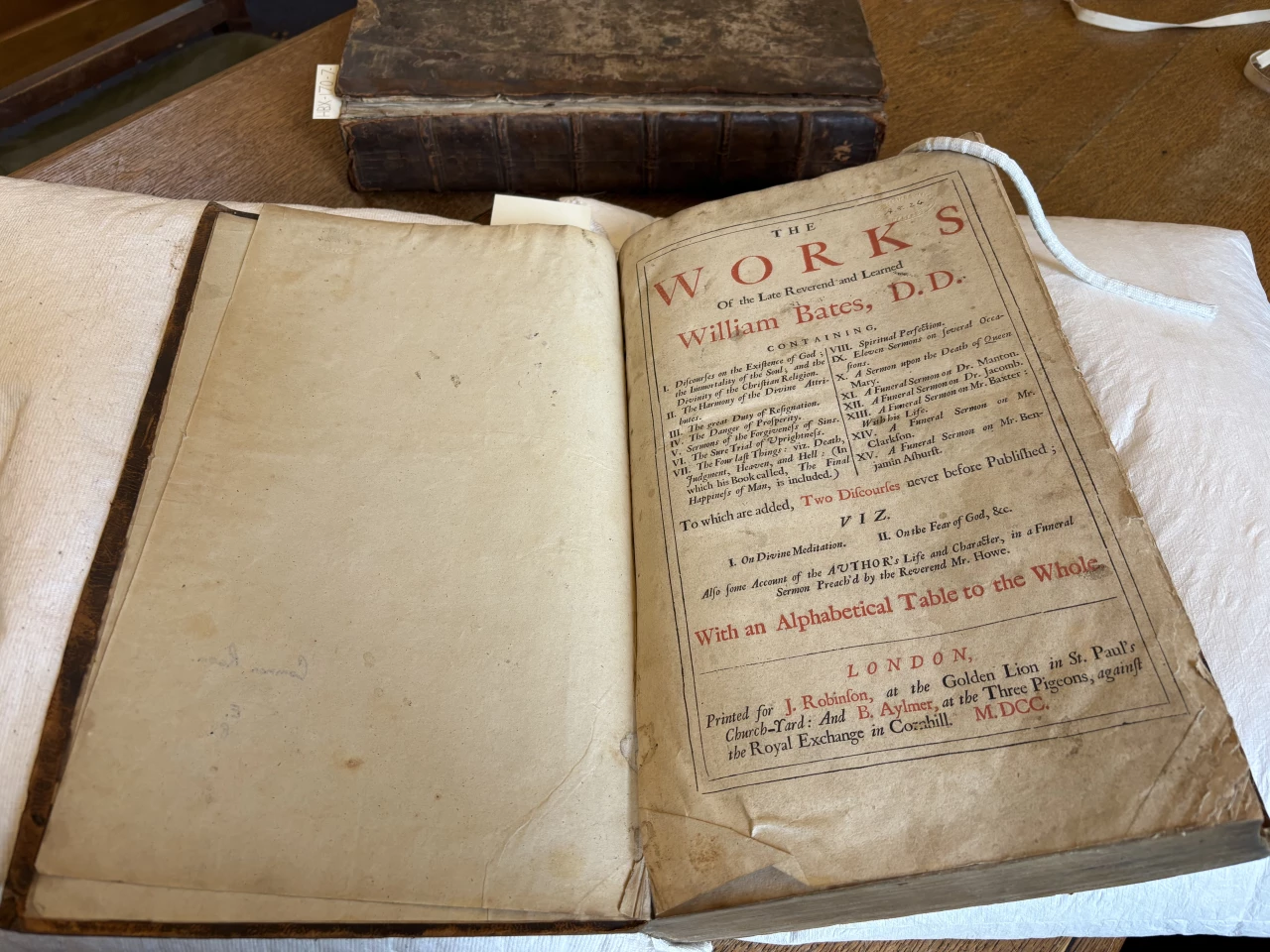

Volume 1 of The works of the late Reverend and learned William Bates, D.D. (1700) held in the Gamble Library at Union Theological College, Belfast.

The coming years saw the great Restoration Crisis (1678–1681) and the subsequent Tory Reaction with it backlash against the Whigs and their dissenting allies. At the Middlesex Sessions in November 1682 Bates was fined £100 for sermons he had delivered the previous month in Hackney. The imposition of these harsh financial penalties was an attempt to crush dissent and to bring about Protestant unity by means of enforced uniformity.

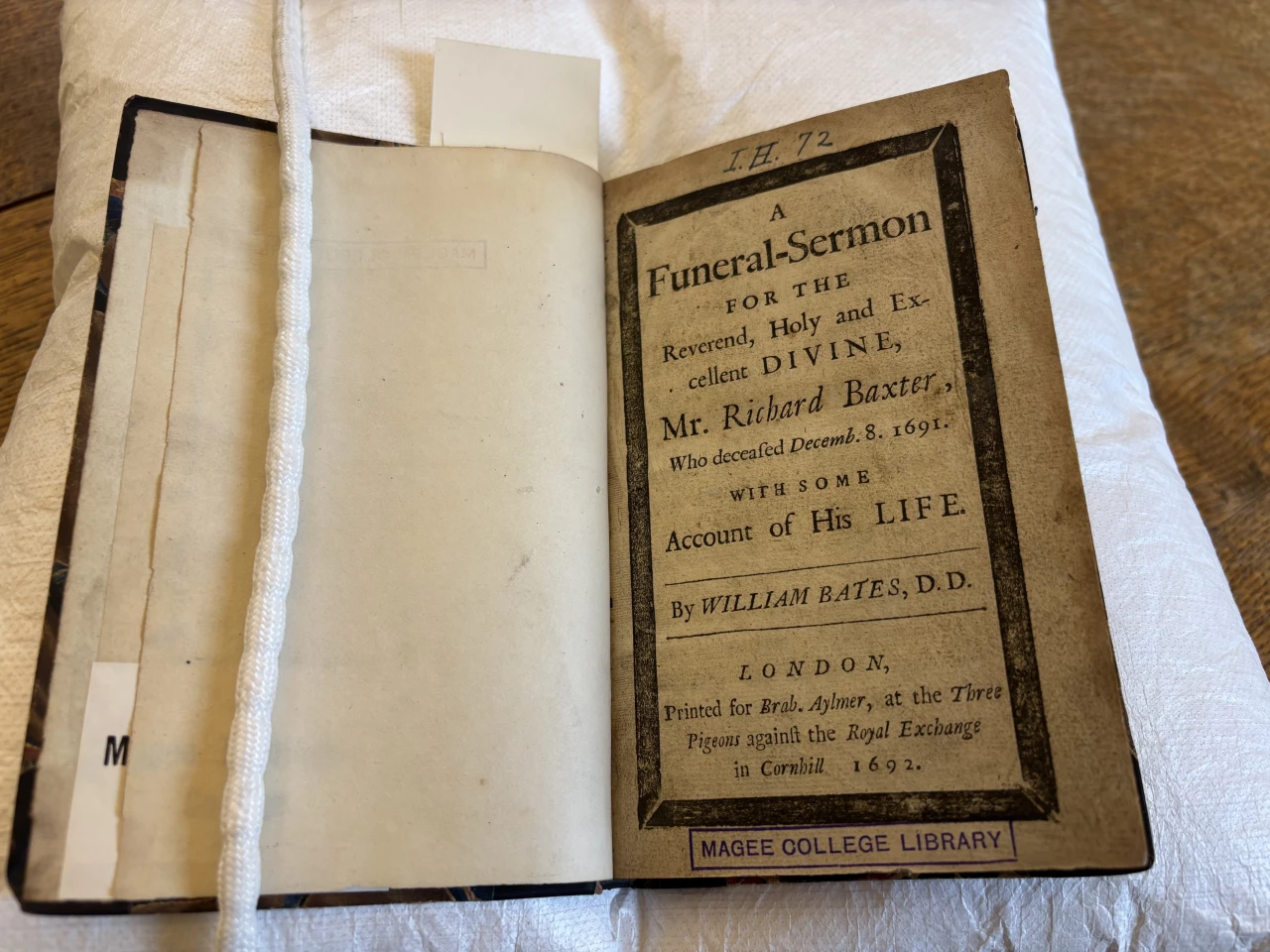

On the accession of William and Mary, Bates delivered an address on behalf of the dissenting clergy, congratulating them and highlighting the plight of dissenters. After a lifetime of political instability this seemed to him like the dawn of a new era. He and other Presbyterians would not take advantage of the freedoms that came with the Toleration Act of 1689. By now any hopes of comprehension within a broad-based national church had ended and Presbyterians and Congregationalists decided that they needed to put aside their differences and work together. In July 1690 the two groups established a fund to raise support for ministerial training and to supplement ministerial stipends. Bates was one of the directors of the fund. In the spring of 1691 many of these dissenting ministers in London reached a formal accommodation in the so-called ‘Happy Union’. At the end of that year Baxter died and Bates delivered his funeral sermon. In the months beforehand he had published The Four Last Things (1691), a pastoral treatment of death, judgment, heaven, and hell.

A funeral-sermon for the reverend, holy and excellent divine, Mr. Richard Baxter (1692) held in the Gamble Library at Union Theological College, Belfast.

The Union of Presbyterians and Congregationalists was not to last because of significant differences and discord between the two groups, especially accusations of antinomianism and nascent Socinianism. A highly symbolic mark of the breakdown came when Bates and the other Presbyterians withdrew in protest from the combined lecture at Pinners’ Hall. Bates had participated in this joint venture with the Congregationalists since its inception, over two decades beforehand, but now the breach seemed irreparable. The Presbyterians established a rival lecture at Salters’ Hall where Bates’s sermons drew large crowds.

In 1694 Bates was certified as ministering in Hackney at a meeting house in Mare Street. He published his high-profile sermon on the occasion of the Queen’s death in 1694 and there is evidence that she had a particular fondness for his books. Bates delivered an address before King William in 1697, championing recent royal victories whilst pressing for further reformation of the nation. He died in Hackney on 21 July 1699. His funeral sermon was delivered by his old friend John Howe who claimed that if Bates had lived in the time of the early church fathers he would have been numbered among them.

His collected writings were published in 1700 and were printed in four volumes in 1815. These doctrinal works combine depth with devotional warmth, especially with their strong emphasis on the character of God. Unsurprisingly, given that he was known as the silver-tongued preacher, his sermons are often elegantly polished, clear, and persuasive. Bates emerges as a man of measure and conviction whose irenic spirit often led him to make serious efforts towards reconciliation and whose spirituality made him remarkably resilient during times of difficulty and persecution. It is fitting that we remember him among those whom J.I. Packer styled as ‘God’s Giants’.

Sources and further reading:

David Appleby, Black Bartholomew's Day: Preaching, Polemic and Restoration Nonconformity

(Manchester, 2007).

Alan Argent, Dr Williams’s Trust and Library: A History (Woodbridge, 2022).

Trevor Cooper (ed.), The Journal of William Dowsing: Iconoclasm in East Anglia during the English Civil War (Woodbridge, 2001).

The Diary of Samuel Pepys, eds. Robert Latham and William Matthews, 10 vols. (London, 1970).

Stephen Wright, ‘Bates, William (1625–1699)’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Gary S. De Krey, London and the Restoration, 1659–1683 (Cambridge, 2005).

A. G. Matthews, Calamy Revised: Being a Revision of Edmund Calamy’s Account of the Ministers and Others Ejected and Silenced, 1660–2 (Oxford, 1934).

John Spurr, The Restoration Church of England, 1646–1689 (New Haven, 1991).

Elliot Vernon, London Presbyterians and the British Revolutions, 1638–64 (Manchester, 2021).

Martyn Cowan

Director of Postgraduate Research and Vice Principal, Union Theological College, Belfast.